It is Monday morning on the fourth floor of the Earth Sciences Centre, University of Toronto, and we are generating random numbers.

It is Monday morning on the fourth floor of the Earth Sciences Centre, University of Toronto, and we are generating random numbers.

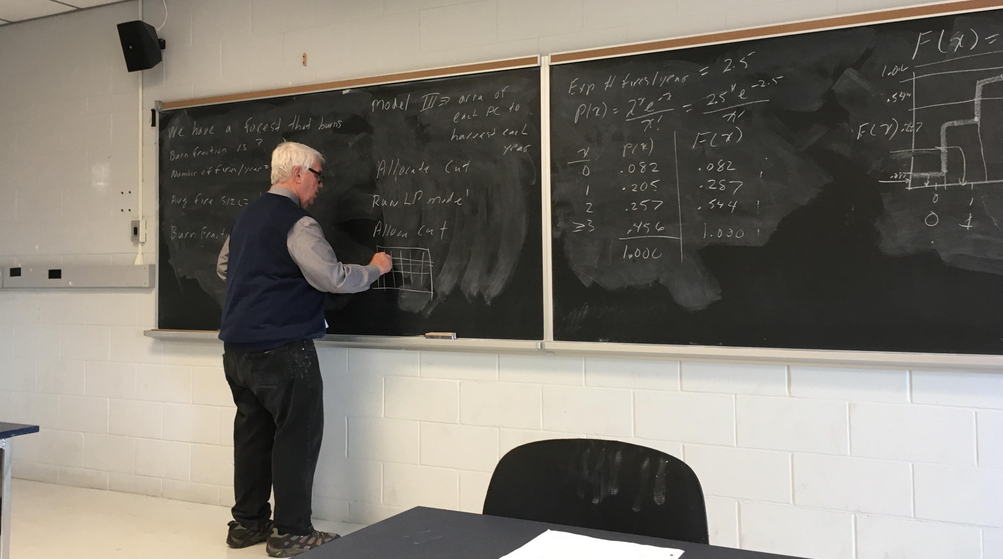

“If we go up here and this is the normal distribution, this is f of x and this is large F of x,” says Professor Dave Martell. “The area of the curve increases and asymptotically approaches one.”

On Monday mornings, such forestry masters students as can make it out of bed (usually about two thirds of the cohort) file into a class called Forest Management Decision Support Systems. On the first day Martell promised us, “This is not a math course.”

After the third class a fellow student whose undergrad is in computer science, turned to me and said, “Who’s he kidding? This is a math course.”

Given that I left math behind more than 30 years ago, this course is so bewildering to me that I at times I just take lots of notes; the words are so crazy that they seem amusing to me.

I can’t say why we are generating random numbers today. Even so, there is a notable purity to the scene.

Often in this class, the blinds are shut so that we can better see the PowerPoint, which, typically, features a blizzard of numbers, most of them indecipherable to me. At least this morning the blind is open, and through the round window I can see snow flutter down on the roofs of buildings at the University of Toronto.

Chalk in one hand, eraser in the other, Martell is rocking the blackboard, old school. He wears a wedding ring, an engineer’s ring and a Fitbit. His attire befits his profession: on top he wears a sweater vest and tie; he completes the outfit with black jeans and hiking shoes. He is engineer above and forester below. As he scribbles, chalk dust covers his hand and part of his sleeve.

“The ability to generate uniformly distributed random numbers is important,” says Martell. “The terminology we use is, x, squiggle, f of x. F(x) is the probability density function.” Numbers and a few words spread across the blackboard.

Now, you may ask what all this has to do with forestry. This is a valid question.

Foresters, like many professionals, like to generate mathematical models to help make decisions about how to manage forests. For example, let’s say jack pine (Pinus banksiana) trees are ready for harvest at age 100. You manage a Crown forest with jack pine aged 0 to 100. You want to cut the stuff that’s mature in sequence at the right time, so in 100 years you’ll have the same total number of pines that you have today.

Based on statistics of how often the forest catches fire, you can also put fire into your model, so you estimate how often, on average, your forest will burn.

Martell, who has been writing scientific papers for 40 years, wrote a paper about a model he fashioned to cut forests in such a way that they are less likely to burn, and wrote a model to suggest how you can cut pine and spruce forests so that you’ll get some wood but also protect the habitat for the woodland caribou.

As for how you do that, well, that’s another story. I cannot pretend that I understand; in fact, my scribbled notes read more like comedy to me than anything else.

“The exponential distribution does not have any possibility for any values less than zero,” says Martell. “Using the integration limit of negative infinity is just the most general case. So let’s talk about the exponential distribution. The age class distribution of a natural forest will tend to have an exponential distribution. Let’s suppose we want to generate exponential random numbers.”

The colleague to my right has gone to sleep. That same colleague compared Martell’s class to Catholic mass: it is morning; an older gentleman talks for a long time. I suppose he used to sleep through mass, too.

Is the absolution that accompanies regular attendance in church worth more than the knowledge of how to generate a large number of random numbers that are universally distributed between zero and one?

I can’t really say. But my fervant hope is that, by the last class of the term, I will be able to ask questions as brilliant as this one, lobbed by a student at the back of class: “Ar you taking the log, or are you taking the natural log?”